Hip labral tears have been diagnosed with increasing frequency. In the past, many patients would have unexplained pain stemming from their hip joint. This was possibly diagnosed as a “chronic hip flexor strain” or “pre-arthritis”. These patients may have been sent to physical therapy, and possibly might have had a cortisone injection, but if the painful condition persisted, there was no other treatment options. This article discussing a frequent cause of non-arthritic hip pain, specifically hip labral tears and Femoroacetabular Impingement (FAI).

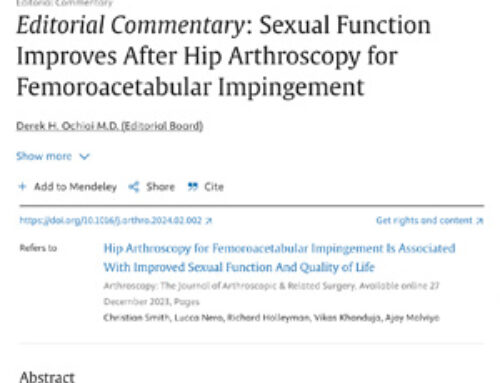

Hip Labrum: The labrum is a rim of cartilage that surrounds the hip joint. It is attached to the socket of the hip, and is confluent with the articular cartilage of the acetabulum (hip socket). The shoulder also has a labrum, and the type of cartilage in a hip labrum and a shoulder labrum are exactly the same. In addition, the knee meniscus (which can also tear) is made of the exact same cartilage as well. (See Figure 1).

Figure 1: Arthroscopic picture of a normal labrum (blue arrow). The labrum attaches smoothly to the acetabular articular cartilage. The femoral head is on the bottom right of the picture.

Hip Labral Function: The labrum “deepens the socket”, thereby giving the hip additional stability. This function can be important in sports/activities that involve extreme ranges of hip motion, such as figure skating, ballet, and gymnastics. There are also medical conditions, such as developmental dysplasia of the hip (DDH), where the hip labrum takes on a more important role in stabilizing the hip, because the socket is too shallow.

Additionally, the labrum helps to protect the articular gliding cartilage of the hip. Statistically, patients who have labral tears in their hip are more likely to get hip arthritis than those without a labral tear.

Mechanism of labral tears: Most labral tears happen because of Femoroacetabular Impingement (FAI). This is a condition that develops usually in a patient’s early teen years, where the hip joint is not a perfectly round on round joint in certain hip positions, such as flexion or rotation. This “out of round” conflict puts increased stress on the labrum, and over time, the labrum can tear. Since most hip labral tears coexist with FAI, their symptoms overlap greatly. Some hip labral tears happen traumatically, from a single one-time trauma, such as a car accident or fall from a height.

Symptoms of a labral tear: Pain from a hip labral tear is most often felt near the groin in the front of the hip. Sometimes, patients will feel pain at the side and behind the hip joint, and this pain may radiate down the thigh. Patients may have pain or a feeling of catching/locking in their hip, such as standing after prolonged sitting. They may have to adjust how they get in and out of cars. They may have pain and/or catching with sports or squatting exercises. They may have pain with prolonged sitting.

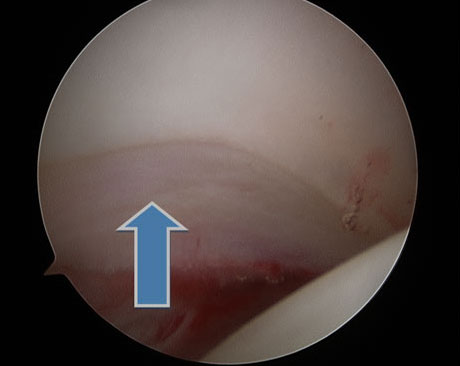

Diagnosis of a hip labral tear: Medical professionals may suspect a hip labral tear based on the patient’s history and symptoms. Then, they may do physical examination tests to further confirm this suspicion. These tests, such as the anterior impingement test, posterior impingement test, McCarthy test, or twist test, involve moving the hip and leg in certain positions, to either evaluate for pain or asymmetry with the non-affected side. X-rays can be extremely useful, as this is the primary way to evaluate FAI. (See Figures 2 and 3)

Figure 2: On left side of screen, normal acetabulum. The anterior wall (red line) and posterior wall (blue line) do not cross. On right, there is pincer type FAI, where the red and blue lines cross.

Figure 3: Typical cam type FAI X-ray finding. The yellow outline shows what the contour of a normal hip would look like.

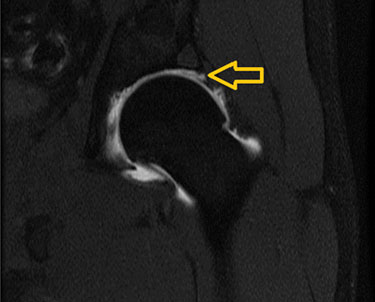

Hip MRI (magnetic resonance imaging) may also be performed. An MRI can demonstrate a labral tear, as the joint fluid would leak into the tear. An MRI arthrogram, where dye is also injected into the hip joint, may show a labral tear more clearly than a non-contrast MRI. (See Figure 4)

Figure 4: MRI arthrogram of a left hip labral tear. Arrow points to the dye leaking between the labrum and the articular cartilage.

Hip arthroscopy is the “gold standard” for diagnosing hip labral tears. However, this is the most invasive test, and is frequently not performed for diagnosis. (See Figure 5).

Figure 5: Large anterior labral tear. Note the separation between the labrum and the acetabulum. Compare this to Figure 1.

Non-surgical treatment of labral tears: Initially, non-operative treatment is preferred. This typically consists of physical therapy for core/gluteal strengthening and some activity modification (avoiding what is hurting). There are studies that show that physical therapy can improve patients’ pain and function. While this may not “cure” their hip, they may feel good enough to resume any activity they desire with minimal pain.

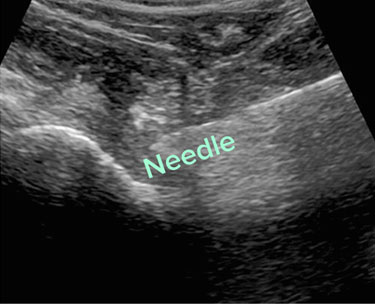

Additionally, your physician may perform a cortisone injection to the hip. Most of the time, this is done with some sort of image guidance, to ensure that the medication is directed inside the hip joint. I use ultrasound guidance for this, which I prefer because of the accuracy and safety (no radiation) of this imaging modality. (See Figure 6).

Figure 6: Real-time ultrasound of a hip injection, with the needle penetrating the hip joint

Surgical treatment of labral tears: While open surgery to treat a labral tear is a viable option, 100% of the hip labral tears that I surgical treat are done arthroscopically, using cameras and small instruments inside the hip joint. “Scoping the hip” means looking inside the joint; there are multiple possible procedures that could potentially be performed during hip arthroscopy. In the past, the most common procedure was labral debridement, or trimming out the torn labrum. While this has the advantage of not relying on the body to heal a labral repair, many studies show that repairing (suturing in place) the labrum has better long term outcomes than debridement. In my practice, labral repair is much more common. The labrum is repaired by drilling anchors into the bone of the socket, and using its sutures (thread) to wrap around and through the labrum to tie the labrum back into place. See Figure 7. When doing a hip labral repair, any FAI would be addressed at the same time. Otherwise, there is a good chance of the repair failing (because the forces that initially tore the labrum would be the same forces causing it not to heal). Click here to watch a peer-reviewed video of my procedure published in Arthroscopy Techniques (https://www.arthroscopytechniques.org/cms/10.1016/j.eats.2014.06.010/attachment/6bf29bdd-386c-4199-af98-f8b285c17885/mmc1.mp4).

Figure 7: Picture of a labral repair. In the picture, there are three sutures that are anchored to the bone, sewing the labrum back to the acetabulum.

A newer procedure to address labral tears is labral reconstruction. This uses a tendon graft to take the place of the torn labrum (See Figure 8). Typically, this is only used for labrums that are so torn and degenerative, such that repairing the labrum will not work to restore normal labral function. Also, I typically use this in patients who may have continued pain after a well done hip arthroscopic procedure, where the previous surgeon may have done a labral debridement.

Figure 8: Labral reconstruction: In this picture, the labrum was not repairable. Instead, a tendon was used as a graft, to reconstruct the labrum.

Hip labral tears and FAI are a frequent cause of hip pain in younger patients. If you have some of the symptoms that I have described, and if conservative treatment has not yet been helpful, then I would urge you to talk to your doctor about hip labral tears and FAI being a possible cause. In addition, I frequently do consultations with patients who are living in another part of the world. Feel free to contact my office to learn more.

Derek Ochiai, MD

Nirschl Orthopaedic Center

1715 N. George Mason Drive, Suite 504

Arlington, VA, USA 22205

(703) 525-2200

Twitter: @DrDerekOchiai

Website: www.Nirschl.com